Split nik, installation at 4th Moscow Biennale 2011, mixed media: 3D model of the Kukarkin Book cover (CNC routered MDF, 5.8×5.8×1.8 m); “Study no.2: “Things and People”” (DVD, 12 min.); Study no.1: 37 pages of the Kukarkin Book (digital prints on lightbond, 60×40 cm each); 3 posters (digital print on lightbond, 100×70 cm each); Kukarkin research group seminar (once a week).

Split nik at 4th Moscow Biennale

Kukarkin seminar

Kukarkin sminar was joined by 5 artists and cultural researchers from Moscow. Seminar took place at Kukarkin house on Povarskaya street.

Lithuanian Embassy

Split nik at 4 Moscow Biennale was kindly supported by the Lithuanian Embassy in Moscow. Members of Lithuanian community attended the opening of the show on September 24 2011.

Kukarkin Emerging – Tracey Warr

Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas’ Split nik installation opened in the Moscow Biennale on 22 September and the exhibition runs until 30 October 2011. Split nik is an installation re-reading a book published by Russian author, Alexander Kukarkin, during the Cold War period, discussing Soviet and Western ideologies in relation to consumerism, design and art. I am an ‘embedded writer’ with the project. The installation is a device to look backwards at the history of the Cold War in culture, focussing on the book Beyond Welfare (The Passing Age in English) by Kukarkin, and also to look forwards from now. The installation consists of three elements:

– a presentation of Kukarkin’s book in Russian, Lithuanian and English,

– extracts from a 1970s Lithuanian film Things and People that humorously examines our psychological and ideological relationships with objects,

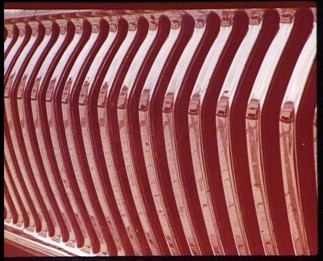

– and a wooden structure resembling convoluted raked seating designed for dialogue.

Installing the work was fraught with drama. It got held up in customs and then lost in the basement of the luxurious Tsum Department Store in Moscow – our exhibition was on the fifth floor. Then our team was beset with flu, a broken hand, and chronic jetlag – nevertheless after a few 24 hour shifts, Split nik appeared – and the relief is evident on the face of architecture graduate, Marius Bliujus, who assisted with the installation.

The fact that the installation specifically addresses Russia and that Gediminas speaks Russian meant that there was a lot of media interest in the work:

http://www.1tv.ru/news/culture/186171

http://www.tvkultura.ru/news.html?id=797368&cid=178

THE FOURTH ELEMENT

The Split nik project assistant, Anna Kotova, contacted Moscow artists via Facebook and Nomeda, Gediminas and I ran a week-long workshop which is the developing fourth element of the work. The participating artists are Elle Gard, Liza Izvekova, Anna Prihodioko, Maria Sokol and Vladimir Smyshlenkov. We discussed the work of Future Studies researchers such as the Global Scenario Group www.gsg.org and Kingsley Dennis and John Urry’s book After the Car (Polity, 2009) and artists considering the future: science fiction, and artists such as Lise Autogena, John and Helen Mayer Harrison, Andrew Sunley Smith, Heath Bunting & Kayle Brandon, Kate Rich, Uta Kogelsberger, London Fieldworks and HeHe.

Talking of Khrushchev and Nixon’s 1959 Kitchen Debate, we wondered why the best conversations always happen in the kitchen. We set them a task to sit in a kitchen (their own, their grandmother’s, a showroom kitchen – whatever they like) and make some sketches of their vision of a future scenario – in whatever form they like: drawings, photo, collage, film, text, sound. We will be posting their developing ideas on the website in a few weeks time. You, the reader, are welcome to submit your Future Casts to us too.

THE PEDAGOGICAL TURN

Elle, Liza, Anna, Maria, and Vladmir are also organising dialogues in Split nik during the exhibition with small groups of people. Documentation of these will follow. Sitting in the Split nik structure we discussed with them the pedagogical turn in art.

Kristina Podesva, The Pedagogical Turn in Art

http://fillip.ca/content/a-pedagogical-turn

Tino Sehgal

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R3qxSjr4eaQ

The Long March (China)

http://fillip.ca/content/the-long-march-project

Platform (UK)

http://www.platformlondon.org/

Jeremy Deller (UK)

http://www.jeremydeller.org

Nomeda & Gediminas’ other projects on http://www.nugu.lt – click on dossier.

We talked about theorists: Clare Bishop’s book Participation and her articles on The Participatory Turn; Christian Kravagna; Grant Kester’s book Conversational Pieces; Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics and Altermodern; Lars Bang Larsen, and then historically Joseph Beuys, Helio Oiticica, Milan Knizak, Marcel Duchamp’s text ‘The Creative Act’, Umberto Eco’s ‘The Open Work’.

KUKARKIN RESEARCH

Meanwhile, we are also progressing our research on Kukarkin himself, leafing through copies of Amerika magazine and Kukarkin’s personnel records, unearthed by Anna. The top floor apartment in Moscow where we were staying was showing the ill effects of a leaking roof and its age. We imagined it could have been Kukarkin’s apartment. The doors squeak painfully, the floors creak, the lightbulbs blow room by room, the toilet leaks, the kettle has a huge crack down one side but still works. Tea is a small mercy.

Kukarkin was born in 1916 at Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod). His parents died when he was a child and he was raised by his uncle, a doctor living in Moscow. From the age of fifteen Kukarkin worked at the factory Dinamo. During 1934-35 he served as secretary in various offices. From 1936 he studied at M. Gorky’s Institute of Literature in Moscow, graduating in 1940. During his studies he published his first critical essays in the magazines Flag (Znamya), New World (Novyj Mir), Literary Observer (Lietarturnoje Obozrenyje). Due to bad eyesight he was decommissioned from army service and worked for various newspapers and publishing houses. In 1943 he was sent by the Communist Party to the Higher School of Diplomacy, which he graduated in 1945. After graduation he began a diplomatic career and was sent to USA.

He was working as an attaché and head of the Press Department at the Soviet Embassy in Washington from September 1945 to August 1946. His time there coincided with the period when Alexander Feklisov was the KGB handler for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg at the New York Soviet Embassy. The Rosenbergs were executed as spies in 1953 and alleged to have given away US atomic secrets to Russia.

In August 1948 Kukarkin was part of a Soviet Delegation visiting the London Olympics at a time when USSR was negotiating terms to join the Olympics – it competed for the first time in 1952. He was a member of the Soviet delegations at the First World Congress for Peace in Czechoslovakia in April 1949; the United Nations Fourth Session September-November 1949; and the Second World Peace Congress in November 1950. The World Peace Council was established in response to fears of a third world war and the threat of atomic annihilation as the Cold War was escalating in Korea. Peace Congress deletes gathered in Sheffield in the UK, including Kukarkin, Picasso and ‘the Red Dean’ of Canterbury Cathedral, Dr Hewlett Johnson, who argued that capitalism lacked a moral basis and the moral impulse of communism constituted the greatest attraction. The British Labour government sabotaged the Congress and it was forced to shift behind ‘the Iron Curtain’ to Warsaw.

Kukarkin was a member of the editorial board of the magazine The New Times (Novoye Vremya). From 1951 he worked as editor of NEWS (Novosty) a newly established English language magazine for foreign countries. He travelled to France as a member of the Soviet delegation to the United Nations Sixth Session November 1951 – January 1952.

From 1953 he continued his literary work. He took a job as head of the Drama Department at the magazine Arts (Iskusstvo). He then disappears from the official records for five years. According to the personnel file during this time he was focussing on literary translations, and writing on Charlie Chaplin.

During 1958-61 he was head of the Foreign Film Department at the State Film Foundation USSR (GosFilmFond). During this time he collected materials for his major work on American film, which was published as part of the larger book: Cinema, Theater, Music, Painting in USA by Znanye (Knowledge).

From 1963 he started research work at the institute of Philosophy at the Academy of Science USSR where he worked until his pension in 1976. During these 13 years he wrote books, essays and articles on contemporary cinematography and critiques on bourgeoisie ideology and culture. The Passing Age – a book for foreign readers was published by Progress, and The Mass Culture of Bourgeoisie was published by PolitIzdat.

He lived his last years with his daughter and granddaughter – who we are hoping to find and interview. We are also very keen to find out more about his diplomatic career and whether there is any information on him, his book designers and illustrators in the archives of Progress publishers. If you have any information on Kukarkin, or would like to comment on his book or Split nik please contact us via this site.

LOOKING FOR KUKARKIN

On Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas’ Split nik

Tracey Warr

Helter Skelter, Sokolniki Park, site of the 1959 Kitchen Debate between Nixon and Khrushchev. Photo: Nomeda Urbonas.

Introduction

In June 2011 I travelled to Russia for the first time, carrying preconceptions largely formed from Martin Cruz Smith novels.

I joined Lithuanian artists Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas and their Russian assistant, Anna Kotova, in an attempt to track down Alexander Kukarkin, an elusive Russian writer from the Cold War era. Our researches became as contorted as the Helter Skelter in Sokolniki Park where Nixon and Khrushchev had their famous 1959 Kitchen Debate.[i] This text is an account of our research, looking for Kukarkin.

Our resulting art project, Split nik, is showing at the Moscow Biennale

23 Sept – 30 Oct 2011

at the Tsum Art Foundation, Tsum Department Store, 2 Petrovka str., Moscow

Open Mon–Fri: 10:00–22:00, Sat–Sun: 11:00–22:00

Nearest Metro Stations: Tverskaya, Teatral’naya.

http://4th.moscowbiennale.ru/en/

We are inviting participation in dialogues about the Cold War and its legacies now, particularly in relation to the role of artists, writers and books. We invite your Future Casts. You can participate in person in the Split nik installation in the Moscow Biennale, or participate by commenting online:

Split nik on Facebook: http://vkontakte.ru/splitnik2011 [Russian]

Or comment here on http://www.vilma.cc/splitnik [English]

Or comment on http://traceywarr.wordpress.com [English]

pdf account of our research so far to download here: LOOKING FOR KUKARKIN

Beyond Welfare

Notes on the translation of the book Beyond Welfare, 1974–1984

by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas

My mother bought this book in the seventies after half a day of queuing. For the generations of the seventies and eighties this book was one of very few sources of information on styles, trends, art and discourse in Western culture, and this fact made the book a hit in the Soviet era. It was first of its kind; offering a vast overview of developments in capitalist culture from a critical perspective, introducing works, names and concepts of western artists, and revealing the schizophrenia and critical discourse within western society.

The official task was to smash the façade of bourgeois culture, unveil its inhuman perspectives, and the inevitable collapse of the value system of the West.

But it simultaneously presented names, contents and concepts otherwise impossible for ordinary people to gain access to.

The first Russian edition was published in 1974, printed in only 75000 copies, and therefore sold out at once. This first edition was inadequate for a large population curious about Western culture. Information had to be leaked in controlled doses, that’s how state control operated, therefore the small number of copies released each time. Within ten years it was translated into many of the languages of the colonized countries, foremost to educate the youth of the Soviet republics. The book was meticulous and rigid , dissecting the rotten body of capitalist culture with the critique that everyone buys. It was the most successful example of its kind.

The book scrutinizes bourgeois culture using quotes from debates at the time in the West. Information was selected from various media sources; affected by the researcher’s strict approach and journalistic style.

A.V.Kukarkin must have had exceptional access to sources for collecting information. I always thought the book was written by some spy, or group of spies who traveled the West, visiting various exhibitions like Documenta, the Venice biennale, MOMA, The Whitney Museum or even the World Expos’. She or he must at least have been a KGB colonel, as only the KGB could have the capacity to produce such analytic work of the scale required to convincingly beat the West at the time. It was impossible for anyone else not only to travel to the West, but also to get access to most of the titles in the bibliography. We had no idea magazines like Amerika and Anglia (both published in Russian), quoted in the book, existed. Besides a great number of references, the book has numerous illustrations, some even in color. Later editions of the book (1977 and 1981) lost that appealing list of illustrations, and at the end the Lithuanian edition (1984), our major source for education, had only poor, bleached, and heavily retouched, small images printed on what is seen today as trendy recycled paper.

Today this book is discarded, disregarded and banned from the public libraries. Politics have changed. It is a Russian book, conceived within the ideological demands of those times. Lithuanian national politics probably considers that this book questions the basic foundation of the culture the country has reconnected to after the years of communism.

The most amusing thing about the book today may be that this heavy, hard-covered book was supposed to provocatively inform Soviet citizens about the repulsive West, and it’s decaying society.

But the book had a totally different effect on the reader. Besides the clichés similar to the Pravda newspaper, one could recognize the heartfelt emotions Mr.Kukarkin deployed in his descriptions of meticulously selected cult images, quotes and discussions from Western sources. It showed you what to desire. It had a stunning effect. Instead of being swayed by critique, you would disregard any social or political context in which the work was conceived, and indulge in the culture so well scrutinized in the book.

Most of the arguments in the original book turned on a critique of art’s autonomy, attempting to reveal the lack of values in the consumer society of the West, obsessed with the accumulation of things and objects. It was therefore also a harsh critique of the “anti humanistic” abstract art famously branded by the US. The culture of the accumulation of things was criticized as lacking any social conscience. It was presented as alienating, as disengaged from any social or political conscience. The Lithuanian translation of the book is almost impossible to understand. For instance; all the names of the bourgeois cultural figures were literally translated from Russian, so one could not relate them to the names we later encountered in life. For example: Brousas Noumenas (Bruce Nauman), Viljamas Berouz (William S.Burroughs) and Sjuzena Zontak (Susan Sontag). Endis Vorolas (Andy Warhol), Teit galerija (The Tate Gallery), Vitnio muziejus (The Whitney Museum). Minimalism translated into miniart, whereas Arte Povera translated into poor art. It created a parallel, a lateral world where names and concepts circulated apart and not in synch with the other reality. It was simply hidden from our eyes, only discovered after the fall of the Berlin wall.

“Campbell’s Soup Cans” was for us only known as an artwork, and what a great surprise to discover the canned food years later! The local censorship in the Soviet republics was so paranoid, people were so afraid of the regime, that translation of the book did not try to clarify facts, on the contrary, similar to the exhaustively retouched images, names and concepts were so filtered that the original meaning or connection was lost forever. The two worlds were split, and the translation brought this reality to the forefront.

To open this book today might evoke some fun, but it is still a complicated process. Much of the critique, neglected at the time for idealizing the Soviet system and perceived as being ideologically commissioned by the Communist party, today reveals a unique debate; questioning hegemony and showing the history of attempts to deconstruct power structures. Now, in the process of translating this book into English, it is not enough to match the Lithuanian with the Russian original (which in it’s turn translated quotes from English), but necessary to test the efficacy of critique in its temporal dimension, suspended between the Soviet times and today.

background for Splitnik

Splitnik is a story conceived in three parts that borrows from the concept of media navigator in form of a viewing device that looks back and forward at the same time. It brings together questions raised during negotiations between two ideologies, with the attempt to study forms of critique in writing, media and design, raising the question of methods, forms and strategies validating such critique nowadays.

Splitnik: rereading of the book, is a translation project of the book “Beyond Welfare” (1974) by A.Kukarkin on cultural criticism and analysis of the culture and ideology of the capitalist world in the later twentieth century.

team

Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas (artists. Cambridge, MA; Vilnius, Lithuania)

Tracey Warr (curator, lecturer. Contemporary Art Theory, Oxford Brookes University)

Julija Reklaite (architect. Vilnius, Lithuania)

Anna Kotova (architecture graduate. Cambridge, MA, Voronez, Russia)

Marius Bliujus (architecture graduate. Vilnius, Lithuania)