Topology of an Island

by Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas

An island is a topologically informed model, one that could be described as similar to a wind tunnel – that is, simultaneously a model of a wind and a lab where the wind is being modeled. The topological interdependency of inside and outside is discussed in the introduction to Spheres (2004) by the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, who outlines a Gilles Deleuze-inspired theory of islands as constituted through two co-dependent factors: isolation and self-expression, where an island results from the action of “’isolating’ and different ways of ‘isolating’ produce different types of islands.”[1]

Deleuze, in his early essay Desert Islands (1953), described how islands are not just created by maritime erosion and terrestrial emergence, but also constitute an “origin, radical and absolute,” in themselves. This happens as soon as the original vectors of creative movement, their “first beginning,” are taken up and prolonged by humans in a “second beginning.”[ii] As in Robert Smithson’s work Towards the Development of a Cinema Cavern, or the Moviegoer as Spelunker (1971), the cave or abandoned mine becomes a modeling ground for production of topological space where the making (modeling) of the carving (mining) process is simultaneously the production and registration of space.[iii]

Juan Navarro-Baldweg’s Proposals for the Increasing of Ecological Experiences (1971)[iv] suggests the application of a climatic control system floating in New York Harbor – “a model of the quasi-closed system – a biosphere, that extends the concept of a park and botanical garden, Tundra, grassland, tropical forest, or desert – to increase social and individual awareness and experience of the major terrestrial ecosystems.” One could imagine the island as a dream of humans, and one could model such topologically complex structure through a system of vectors, flows, proximities, and loops that turn reflexivity itself into a mechanism.

Paul Virilio develops an inspiring articulation of the topological model that suggests a “move from topology to tele-topology… whereby space gradually folds in on itself, collapsing local territories into the space of the city-world… In what sense can one still ‘build’ something – anything – when interfaces replace surfaces and instant feedback shrinks the planet to nothing?”[v]

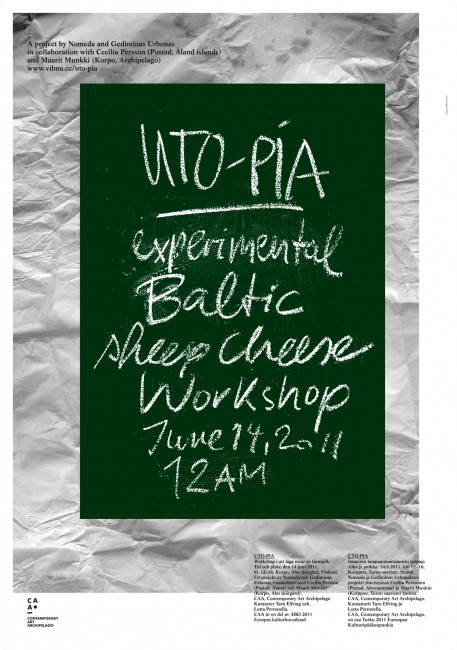

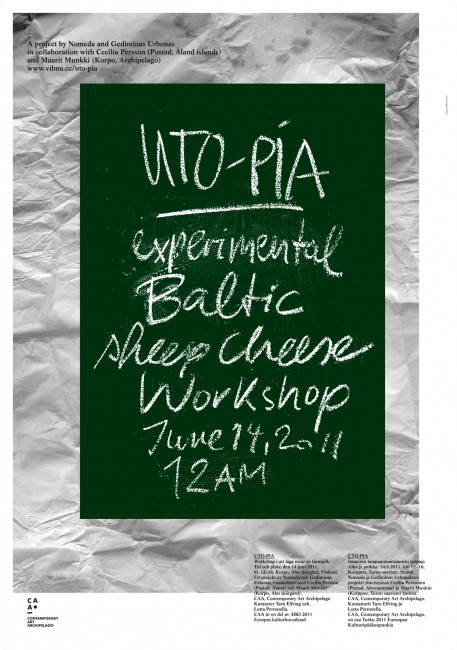

The Uto-Pia project takes on this topological entanglement and suggests a model within an emerging dialogical sphere between the Contemporary Art Archipelgo (CAA), the art project and Turku Archipelago, a constellation of more than 40,000 islands in the northern part of the Baltic Sea – one of the most polluted seas in the world. In between the model and its modeling site, the island speaks to the ideal condition (a dream?) that can be achieved (modeled) perhaps only in such a lab situation, given the scale and “insular climate” – a perfect continuum between geography and human imagination.

Uto – the most remote (and strategic!) island from a myriad in the archipelago – is a man-made fortress with its signifiers crafted for orientation and disguise: a beacon to guide ships charting international waters, a maritime defense fortress and a garrison as sources of infrastructure for natural and civilian life. For the project, this topology is derivative; it is a constituency that suggests Uto as the core part of the project’s title.

Pia – the second half – is the name of a Finnish woman who has four sheep. She lives with her sheep on, Korpo one of the bigger islands in the archipelago. To get there one needs a boat or needs – if you read to the end of this essay – a bridge – that is, a shortcut between Uto and Pia, a hyphen, an abstraction, a transitional object. The transitional object is borrowed from psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott.[vi] For Winnicott, the transitional object designated “the intermediate area of experience, between the thumb and the teddy bear, between the oral erotism and the true object-relationship, between primary creative activity and projection of what has already been introjected. Not necessarily a thing at all, the transitional object is more often an action, a sound, or some other phenomena.”[vii] It is the choreography that sets objects in motion.

What is discussed here is a non-representational art practice, where choreographic forces are vectors organizing the spatial, and where the concept of time plays a rather critical role.[viii] The transitional object is the accumulation of these forces, pointing out the aesthetics of the environmental feedback loops that chart spheres in action.

Infrastructure of War

“Myths thus tell us that islands – be they spent projectiles, coffin lids, fishes turned to stone, or earth thrown down from the sky – are the result of a practice, the outcome of application of a technique. With the advent of the Enlightenment, the casting of the archaic island became the technical-political designing of an island; and the island definitively shifted “from the register of the ‘found’ to the register of the ‘made’.”[ix]

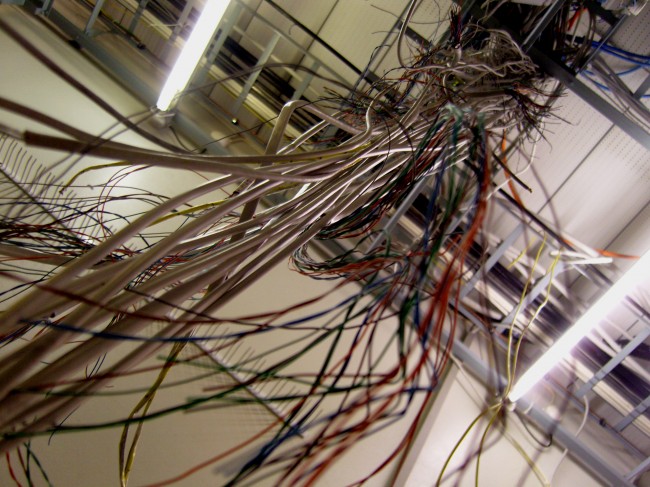

Through a history of being under siege, the islands of the Turku Archipelago naturalized an alien body of military architecture. Islands are subjugated and supplanted by the infrastructure of war. The rocks and waters in between are appropriated to construct lines of defense and deception, to take over control of the landscape and vistas, creating places to hide and to observe. Defensive structures are built by carving out tons of rock, and pouring concrete to form a system of tunnels, caves, bunkers, and hideouts, a military fortification that through centuries of development have radically reshaped what we would call landscape. This landscape raises the question of what the natural actually means. In her writing on Second Nature, Felicity Scott Brown discusses implications of Hans Haacke’s early systems-based works and says that “these works show that relationships between humans and environments are never natural; they are historical, institutional, and political.” Further she continues: “at stake is what steps in to mediate those relations – art, architecture, technology, business, management, behavioral science – and to what ends… to make environmental ‘lines of force’ visible today may be far more difficult than McLuhan could have ever imagined: Communication technologies have not only become smaller and more embedded within our everyday environments, but given their ubiquity, speed, and ability to know us, they now seem all but natural.”[x] For perhaps 600 years this archipelago has been shaped by human imagination, engineering, and craft, making it a stronghold on the Baltic sea – and at the same time, producing a system of relationships with war and communication technologies. These relationships could be articulated as ecosystems with their own specific environmental homeostasis.[xi] The military presence on the Baltic Sea made an impact on several levels but ultimately on the level of chemical processes that map onto the environment. The exchanges between the military body and other spheres of life register distillation, fermentation, mildew, and other processes similar to food making. Like any infrastructure, this system of constant flux provides energy, water, telecommunications, and other flows collapsing distances and proportion of this isolated environment. With the development of remote sensing and remote viewing technologies, the Finnish navy is leaving the islands. Through the centuries, they have built interdependency between the landscape, army, and civic life. We challenge their departure with the question: How do we transform that military infrastructure into the civic life?

Red Herring Technique

In Turku we met Kaj Kivinen, an engineer retired from the Finnish company Sonera, who told us stories about the archipelago as a testing ground for experiments in telecommunications and networked technologies.[xii] These memories provoked us to search for temporal sediments and hidden curves in the recent histories of the Cold War as they relate to local ecologies, memories, the human milieu, and the landscape.

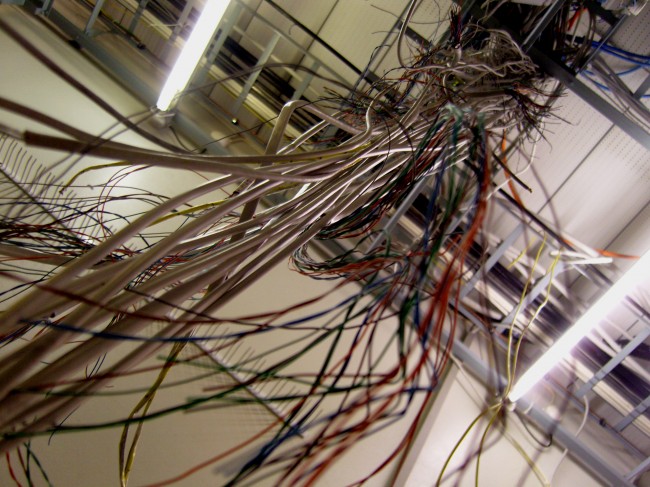

On Korpo Island, the Finnish Center for Biosphere Research is located on the top of what is called the Telegraph Hill. Next to the Center there is an entrance to the secret bunker that, deep down in the rock, hosts the infrastructure of a direct line between Moscow and Washington.

During the peak of the Cold War, the Cuban missile crisis revealed a need for direct communication infrastructure between the two superpowers, the USA and the USSR. It took Washington nearly twelve hours to receive and decode Nikita Khrushchev’s 3,000 word initial settlement message, a dangerously long time in the chronology of nuclear brinksmanship. By the time the White House had drafted a response, another message from the Kremlin had been received demanding US missiles be removed from Turkey.[xiii] It was then that Soviets and Americans agreed to install a dedicated telephone line to secure direct conversation between Washington and Moscow. Called the Red Line, it navigates Baltic waters, coming to the surface in Korpo island where the monstrous concrete bunker casted into the Finnish rock – a hidden telecommunication hub – transforms the island into a deadly military weapon. Since the end of the Cold War, it has been in the possession of the local telecommunication company, kept classified and until recently maintained with fully functioning systems of ventilation, electricity, and heating. For future wars? As a metaphor of suffocation? No. That is the inevitable condition such ecosystems of fear demand: once built, underground bunkers must be maintained in order to prevent them from falling into dangerous ruins. And despite the people living and working around, this bunker has been maintained and kept secret. Its bunkeresque spatial logic speaks to us as being the most remote (de-territorialized) and at the same time the most connected (re-territorialized) sphere.[xiv]

Choreographies of the Biosphere

According to Vladimir Vernadsky, “the biosphere has existed throughout all geological periods, since the most ancient indications of the Archean. In its essential traits, the biosphere has always been constituted in the same way: this singular chemical apparatus, created and kept active by living matter, has been functioning continuously in the biosphere throughout geological times, driven by the uninterrupted current of radiant solar energy. This apparatus is composed of definite vital concentrations which occupy fixed places in the terrestrial envelopes of the biosphere, and which are constantly being transformed.”[xv]

Water permeates all layers of the biosphere and caries flows of data to function as a recording device. Through sediments, accumulated on the seabed, it registers an enormous archive, a memory of exploitation and abuse, capturing diverse human interventions. The Baltic waters recall history, the time after WWII when the chemical weapons of Europe were buried by the Allied forces at the bottom of the sea. The huge repositories of arsenic sealed in metal containers were dumped from the boats in neutral waters. Histories of war, conquer and colonization of new territories goes hand in hand with the histories of industrialization or industrial agriculture that spat out tons of pesticides and nutrients, making a lasting effect on the ecology of the sea and turning vast territories of seabed into a dead zones. The bottom of the sea is charted and parceled by telecommunication networks and cables, as well as gas and oil pipelines. These infrastructures constitute dependencies and feedback loops, or as Virilio suggests: “contraction of the space-time of political or military action is also a contraction of the day-to-day life of individuals.”[xvi]. Therefore one must see sheep, that universal symbol of innocence, grazing in their meadows as part of the same space-time circuit, the same chemical apparatus. Meadows are places on the island where the eco-systematic balance can be re-established.[xvii] The body of every sheep is a small refinery and telecommunication hub generating exchanges that take place between microbes thriving on the sheep’s body and the ones in the soil where the sheep grazes. The liquids facilitating this process instill the landscape with human affect.[xviii] The historical landscape – with sheep as an integral part of it – was altered with the industrialization of farming, collectivization, and mass production in agriculture, ultimately also by telecommunication technologies. Nowadays, the sheep grazing their meadows are supported by EU programs that encourage their presence on the landscape, whether as part of beautification or as part of technology to re-establish ecological balance.[xix] There are several thousands of sheep on the archipelago, but after years of militarization, no dairy tradition remains. Sheep are not even used for wool – only the harvesting of their meat provides a substantial revenue.

Cheese as an Intermediate Object

To paraphrase Felix Guattari, the reorienting of a military infrastructure cannot come without the recomposing of subjectivity and the reformation of capitalist powers. Technocratic adjustments alone will not suffice. Guattari devises an ecosophy that would work simultaneously on three registers: mental, social, and environmental. “More than ever, today nature has become inseparable from culture. If we are to understand the interactions between ecosystems, the mechanosphere, and the social and individual universes of reference, we have to learn to ‘think transversally.’”[xx] Thus the crucial component in Uto-Pia is the distance and relation to animal that should be retained on a micro or personal scale, as opposed to a militaristic, industrial, and representative macro scale. The milking process allows human to physically retain and regain the lost distance to themselves, to the territorial bodies of the geographic habitat, and to the civic life.

The idea of the pollution of distances is discussed by Virilio, who describes the grey ecology model of the space-time relations between the human body and real-life proportion. He argues that space-time vectors constantly compress that proportion, aiming the retention of the distances of the world proper. “The space-time of the local distances in which ‘I’ live is inscribed in an apprehension of the global distances which surround me. The world proper is composed within me of the speeds of transference and transmission that have constructed me—my body proper inside the world proper. This situation of interference between local distances and global distances, which is modified by speed, explains the present contraction. It is in the end a contraction in the sense of a compression between the exterior and the interior of the body proper. The body proper no longer has the same relationship to the world proper as it did during the Crusades or in the days of Marco Polo.”

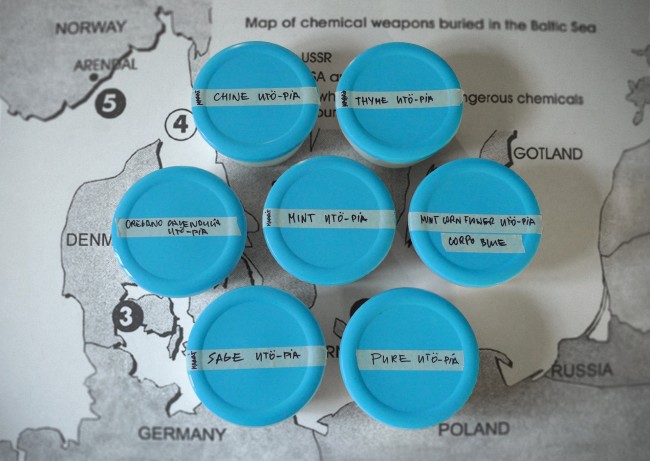

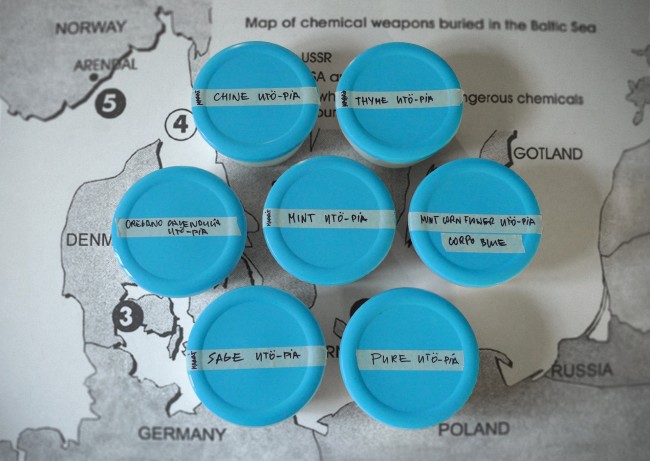

To address the contamination of “the real-life geospheric proportions,” the Uto-Pia suggests the idea of the wirelessless[xxi] cheese – the product that maps zones out of the sight of the radar. The making of wirelessless cheese is creating a model of the body’s relation to the landscape and is simultaneously remodeling the space of relations within the economy of the biosphere where “the pollution of temporal distances” is negotiated. Following this logic, the proposal for the army was drafted – not to leave the islands, but engage with the conversion by milking the sheep and making the cheese, transforming the bunkers with their controlled climate into cheese caves.

Sheep milking is a lost tradition in the Northern part of Europe. With the EU legislation, new members of the European Union have quotas on many things, including the number of sheep. For example, Lithuania signing the agreement to join the EU (in 2004), accepted the condition that they will keep in total seventeen thousand sheep. As there were already more than fifty thousand sheep in the country, some herders had to re-register sheep as goats to bypass the legislation.[xxii] The tradition of dairy-sheep farming has been lost in the Baltic region. Of all the food stores and farmers’ markets across the Turku archipelago, none had locally produced sheep-milk cheese. If one would look for dairy-sheep farmers across the Baltic Sea, one would find only two in Lithuania, none in Latvia, one in Estonia, perhaps several in Poland and Northern Germany, and six in Sweden. The only such farm to be found in Finland is the one of Cecilia Persson, a farmer living in the neighboring archipelago, called Aland, in a territory in fact autonomous from Finland.

Cecilia moved to the Aland Islands without much experience in farming. From her uncle she inherited Skimra, a cow farm that she rebuilt and re-engineered to adapt for a sheep farming. Taking knowledge from advanced dairy-sheep farms in Sweden and Germany, she developed her own recipes of cheese making, infused with local Baltic herbs. Her signature sheep-milk cheese comes with Baltic clover. Cecilia joined the Uto-Pia project as an interlocutor to instruct participants of the First Baltic Sheep-Milk Cheese Workshop and to experiment in making a special recipe of sheep-milk cheese for the project.[xxiii]

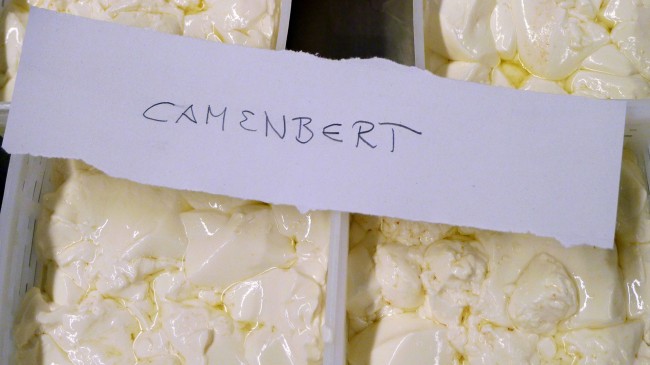

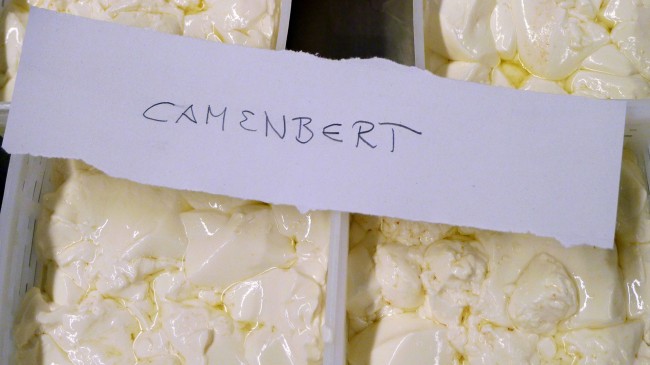

As the summer comes late to the northern part of the Baltic (and Alands too) and the potential milking season at the Cecilia’s farm starts much later, the material for the workshop – the sheep milk – had to be brought from the other farms around the Baltic Sea. It took weeks to milk those few sheep to gather the required amounts from several farms. Milk had to be frozen and smuggled for the workshop in a small portable fridge that fits into a car. The milk of sheep thanks to its particular chemical structure, similar to a human milk, allows it to be frozen and defrosted without losing qualities conditional to the production of cheese. Frozen pieces, collected almost like ammunition, were brought by boat to the island, to the local school kitchen for an experimental production joined by local participants: some just starting as farmers – some working with taste or on environmental issues – coming together to test the idea of an artistic edition, all curious about the alchemy of transforming the food-making process into networked experiences; each contributing with their own story to the pool of local knowledge; sharing their recollections on histories of war, economy, cybernetics, or local ecology.

Cheese making involves ripening and maturing – aspects of time and transformation, and matters that work with organization of space. One has to engage with culturing, bacteria, rennet, mould-ripening, enzymes, or fungi. Camembert or Roquefort require to be ripened in the cheese caves, so the bunkers of Turku archipelago could be turned into vessels with their own unique cultures, spores and spectres, like stomachs in the landscape with their own wild bacteria to induce fermentation and coagulation.

The Bunker-esque

In his years of architectural studies Virilio was fascinated with bunkers left behind by the Second World War. Bunkers as forms of defensive architecture inspired him to think of a tactical forms of resistance and warfare as they suggested the obstacle in the paths of man or the oblique. Drawing on the knowledge of Situationists’ practice where derive stands for “a mode of experimental behavior – a shortcut through the varied ambiances of urban life,” Virilio suggests the oblique function to enable the shift, to dis-balance the trajectory of the mundane, to transform the body of the beholder. The notion of the inclined plane that can be understood as both – as metaphor and as physical object. It sets the human body in motion transforming it into the one of a dancer to release choreographic forces that restructure ourselves and our relations to space.[xxiv]

So the questions is here of a stage, a platform, where the choreography can engage time and space. Virilio mentions Michel Siffre, the “cave man,” who experimented with life in a cave in order to live outside of time. Siffre enclosed himself in a cave “to lose his circadian rhythms, to break the body’s relationship to time, bounded to the twenty-four-hour cycle.” As Virilio suggests “one can not develop a non-Euclidean architecture unless entering into space-time.” Like the cave, the bunker is the oblique that integrates time into space. Being at the same time the most remote place on the island, the bunker is the place that once was most connected. Through the Mobius-like space-time surface, the bunker (the cave) choreographs bodies to move through the space, so their gestures raise the question of time. By entering the bunker one engages the stopping of time and playing with proximities to the environmental lines of force.

The inquiry into the topology of the island is conducted through the movement realized in three acts: the First Baltic Sheep-Milk Cheese Workshop, the Wirelessless Cheese, and the Bunker Tour. The bunker on the Telegraph Hill was turned into the stage for the script-based choreographies performed by the protagonists – the residents of the Uto-Pia – the participants, whose stories, documented through a series of video interviews and supported by the fictional archival materials, chart proximities between the body and the landscape: Kaj Kivinen, a retired engineer, the man behind most of the telecommunication experiments of the Cold War era, nowadays dedicated to the alternative tours and preservation of micro narratives as they belong to the histories of Turku; Katja Bonnevier, a biologist, weaving passionate lines on the significance of the meadows in reconstructing the powers of the biosphere; and Maarit Munkki, a historian and a sheep owner currently undergoing the process of becoming local on the island, who started “a small scale” organic farm in “search of a life-form,” that she articulates as “a quality time with the earth, plants, and animals.”[xxv]

The tour through the bunker, guided by the three participants, navigating layers of audiovisual interventions in the bunker space, is conceived as a form of inquiry that explores the notion of “gray ecology.” Reflecting on the topological model, suspended between the actual – the bunker – and the virtual – “the tele-space that carries all the senses at a distance” – it works with a stereo reality that the bunker tour makes into the site of action. The choreographic modeling of the Tour engages the space-time through direct, slow and haptic interactions between the body of the audience and the landscape of images projected in the space of a bunker. In the center of this choreography there is a navigator – the wirelessless cheese – a body (within the body of the bunker) that registers that “real time is a determining element of power.”[xxvi]

[1] SLOTERDIJK, P. (2004) Sphären III: Schäume. Plurale Spharologie. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

[ii] DELEUZE, G. (2004) Desert Islands. In Lapoujade, D. (ed.) Desert Islands and Other Texts: 1953-1974. Los Angeles – New York: Semiotext(e) p. 9-14.

[iii] CHAMBERLAIN, C. (2008) The Moviegoer as Spelunker. Cabinet, The Underground. Issue 30 (Summer 2008).

[iv] KEPES, G. (1972) Charles River File. CAVS archive, School of Architecture+Planning, MIT, Cambridge, MA.

[v] VIRILIO, P., LOTRINGER, S. and TAORMINA, M. (2001) After Architecture: A Conversation. Grey Room. No.3 (Spring 2001). p.32-53.

[vi] WINNICOTT, D. W. (1971) Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock Publications.

[vii] VARNELIS, K. and SUMRELL, R. (2010) Personal Lubricants: Shell Oil and Scenario Planning. In Ghosn, R. (ed.) New Geographies: Landscapes of Energy. (volume 2 February 2010). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

[viii] Mark Goultorpe professor of architecture at MIT suggests the idea of “autopoetic generative processes” as found in the work of Bill Forsythe and in Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce.

[ix] SLOTERDIJK, P. (2004) Sphären III: Schäume. Plurale Spharologie. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp

[x] SCOTT, F. ( 2013) Limits of Control: On Rain Room and Immersive Environments. ArtForum. (September 2013)

[xi] KEPES, G. (1972) Art and Ecological Consciousness. Arts of the Environment. Henley UK: Aidan Ellis

[xii] The interview with Kaj Kivinen, retired telecommunications engineer and tourist guide. (2011) Video Interview. Directed by Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas. [DVD] Vilnius-Cambridge: Urbonas Studio.

[xiii] WIKIPEDIA [Online] Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moscow–Washington_hotline [Accessed: 21st July 2011].

[xiv] DELEUZE, G. and GUATTARI, F. (1972) Anti-Œdipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Vol. 1) . London and New York: Continuum (2004)

[xv] VERNADSKY, V. (1926) The Biosphere. In Kastner, J.(ed.) Nature. Documents of Contemporary Art. London: Whitechapel Gallery; Cambridge: The MIT Press (2012). P. 79-80.

[xvi] VIRILIO, P., LOTRINGER, S. and TAORMINA, M. (2001) After Architecture: A Conversation. Grey Room. No.3 (Spring 2001). p.32-53.

[xvii] The interview with Katja Bonnevier, biologist and coordinator for Archipelago Sea Biosphere Reserve. (2011) Video Interview. Directed by Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas. [DVD] Vilnius-Cambridge: Urbonas Studio.

[xviii] The idea of micro level communication between the sheep’s body and meadow (the soil) is inspired by Claire Pentecost suggesting “commensal association” between bacteria (species). Available from: PENTECOST, C. (2012) Report from Underground. In Christov-Bakargiev, C. and Martinez, C. (eds.) dOCUMENTA (13) Catalog 1/3: The Book of Books. (2012) Ostfildern : Hatje Cantz Verlag.

[xix] The use of sheep is seen as part of management of meadows, the biodiversity-rich ecosystems and is supported by EU programs. Available from: EU Commission (2009) CAP Reform: Rural Development. FactSheet. Directorat-Generale for Agriculture, Brussels, Belgium.

[xx] GUATTARI, F. (1989) The Three Ecologies. London and New Brunswick, NJ: The Athlone Press (2000)

[xxi] The notion of Wirelessless as oposed to Wirrelessness is a state of being not connected to objects and infrastructures knowing exactly how or where. The Urban Dictionary suggest that Wirelessless is “ When you have no wireless connection” [Online] Available from: http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=wirelessless

[xxii] The interview with Kristina and Juris Milisiunai, dairy sheep farmers. Dvargaliai village, Lithuania (2011) Video Interview. Directed by Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas. [DVD] Vilnius-Cambridge: Urbonas Studio.

[xxiii] The interview with Cecilia Persson, dairy sheep farmer. The Skimra farm, Aland islands (2011) Video Interview. Directed by Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas. [DVD] Vilnius-Cambridge: Urbonas Studio.

[xxiv] VIRILIO, P., LOTRINGER, S. and TAORMINA, M. (2001) After Architecture: A Conversation. Grey Room. No.3 (Spring 2001). p.32-53

[xxv] The interview with Maarit Munkki, historian and sheep owner. Korpo island, Finland (2011) Video Interview. Directed by Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas. [DVD] Vilnius-Cambridge: Urbonas Studio.

[xxvi] VIRILIO, P., LOTRINGER, S. and TAORMINA, M. (2001) After Architecture: A Conversation. Grey Room. No.3 (Spring 2001). p.32-53